The term social business first emerged in Nobel Laureate Prof. Muhammad Yunus’ book, ‘Banker to the Poor,’ wherein he describes the concept of social entrepreneurship.

The term social business first emerged in Nobel Laureate Prof. Muhammad Yunus’ book, ‘Banker to the Poor,’ wherein he describes the concept of social entrepreneurship.

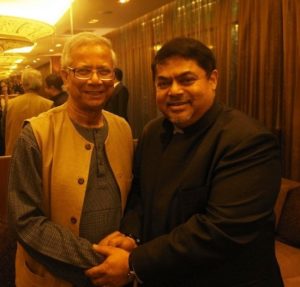

It has since then taken on a life of its own and in effect has become a new paradigm of study and practice in the world of business, banking and enterprise. Interestingly enough, when Yunus first envisioned social entrepreneurship, he explained to me at a recent meeting in Singapore, that he did not factor social business as its eventual evolution. Certainly not in the form it is today.

However, clearly, as he built Grameen Bank on the foundation of microfinance, and as the practice grew, he began to realise the limitations of drawing further investments without capitalism as its fundamental motive. Thus, social business as the name implies is actually where capitalism meets socialism.

Here, Yunus envisions a world where capitalists would invest without desiring a need for a return in terms of dividends or possibly even profits. Instead, the motive here for the investor would be a desire to bring about a social or communal change in society. Thus, while it is not charity, it is not entirely a profit driven enterprise either.

A successful example of a social business in practice since 2006 is Grameen Danone Foods in Bangladesh, a joint venture between French yoghurt maker Danone and Yunus’ own Grameen Bank. Groupe Danone is the world’s largest yoghurt maker and one of the biggest companies in France, with some $21 billion in sales annually. Grameen Danone produces low cost yoghurt fortified with vitamins and minerals generally lacking in the diets of the area’s poorer children. The company has set up factories, distribution systems and even retailing down to the micro level wherein the community plays an integral part.

To make the yoghurt affordable to the poor at who it is aimed, the company built a far simpler, lower-cost, factory, and relies on cheap labour at local wages. What the factory lacks in size, it makes up for in ease of use; workers simply don’t have to be as skilled. Danone expects the enterprise to eventually run at breakeven or better, but any profit will be reinvested in similar projects. Grameen and Danone have proven with this successful project that the concept of social business is one that is worth looking into.

In this jargon filled world of CSR and corporate philanthropy, corporations are struggling to find a productive and effective way of giving back to society without it being charity.Charity has not worked and will not work. It is at best a crutch. Charity will eventually become a wheelchair and it rarely takes a patient to the point of standing up and walking on his own. Poverty is the most humiliating of all crimes and it is prevalent in one-half of humanity. Three billion people in a world population of six billion live below the poverty line. No country is exempt from poverty. Even the mighty US have at least 36 million people below the international poverty line.

Sadly, it is not a problem that seems to get any smaller or weaker, nor has the world thus far been able to get a grip on it. Social business may not be the magic bullet, but it is certainly the first step on an evolutionary process that will and should take us on to a better path to the right goal. Yunus explains that 58 percent of Grameen borrowers have already crossed the poverty line. Bangladesh has been reducing poverty on an average of one per cent a year since 1990, and since 2000 by more than two per cent a year.

Historically, man has been an agricultural creature. With the advent of manufacturing and technology, all that we have been able to do is reduce the need for manpower. The world of the future is one where there is bleak hope for any kind of solution to the high rate of unemployment. The need of the hour is to find solutions and find them fast. The mega corporations have put aside millions, and the UN has probably spent billions through its multiple organisations towards poverty alleviation projects. Nevertheless, it seems like we are simply sinking into quicksand with no firm footing underneath.

The rationale of social business is to provide not just sustenance but a means of employment for the myriad of millions out there. It is to provide them with a gainful methodology that will enable them to contribute towards society and build homes for themselves and their families. The concept itself is sound. The profits earned from the ventures that social business is wrought around will be sunk back into expansion and growth. Hence, the only funds that need to be taken out are of the original investment, leaving behind a self-sustaining business model.

In principle, this should work and has been implemented successfully as in the case of Grameen Danone. In practice, a lot of effort needs to be put in closer to the ground. Social enterprises have to compete in the commercial market and face the same challenges and risks as all businesses. They also need to be pragmatic about the limitations of market economics and persistent about finding ways to use markets to empower the poor. The greatest challenge for social entrepreneurs lies in persuading all other sectors to reinforce and support them. Most governments, businesses, bilateral institutions, foundations, and the civil sector have not yet caught up with this emerging field, and they too often stand in its way.

I truly see the vision of Prof. Yunus in conceptualising what is potentially a solution for our socio-economic ills. He has begun a noble cause and is now on a quest to seek funders from across the first world and Asia to develop and propound this quest. I for one will be with him.

(The writer is a leading Asian businessman, bestselling author and speaker. He is also a major investor in the Colombo Stock Exchange.)